Archive Monthly Archives: September 2016

Information Sheet – Electric Bicycles

Electric Bicycles

What is an Electric Bicycle?

An electric bicycle (or e-bike) is a bicycle with a motorised assistance.

There are two types of legal motorised bicycles:-

- Those that require the cyclist to move the pedals to maintain electrical assistance (pedalec); and

- Bicycles with a handlebar throttle, that allow a cyclist to travel without using the pedals1

Design Rules / Requirements

The Australian Design Rules (ADRs) are national standards which dictate vehicle requirements. For vehicles manufactured post-1989, the application of the ADRs is the responsibility of the Federal Government pursuant to the Motor Vehicle Standards Act 1989 (Cth).

In 2012, changes were announced to the national vehicle safety standards in relation to power-assisted bicycles.

There are two types of legal motorised bicycles in Queensland (as described above) and the requirements vary for each. The pedalec type of bicycle must comply with the European Standard for Power Assisted Pedal Cycles (EN15194). The bicycle can have a maximum of only 250 watts of power and must be marked to show that it complies with the standard.

Bicycles with a handlebar throttle can have a motor that generates no more than 200 watts of power. If it is capable of generating more than 200 watts of power or has an internal combustion engine, then the bicycle must comply with Australian Design Rules for a motorbike and cannot be ridden on roads or road-related areas if it does not comply with these standards.

Do riders of Electric Bicycles have to comply with the Road Rules?

Yes. Bicycles are considered vehicles under legislation in Queensland, and so riders must obey the general road rules as they apply to vehicle operators.

1NB – The pedals should still be the primary source of power for the bicycle. If a rider can complete a journey without using the pedals and powered solely by the motor, then this would not be classed as a motorised bicycle

By Emily Billiau and Gemma Sweeney

Case Study – The Motorised Bicycle

Hendricks v El-Dik & Insurance Australia Limited T/AS NRMA Insurance (No 4) [2016] ACTSC 160

This decision involved a Plaintiff cyclist who was injured when he was struck by a motor vehicle driven by the First Defendant.

The Plaintiff had been cycling home from his workplace. His route took him along a cycle path which included a section that cut across a number of driveways, including the driveway of the First Defendant motorist.

As the Plaintiff cyclist approached the driveway of the First Defendant, the First Defendant reversed out of his driveway and into the path of the Plaintiff cyclist – causing the Plaintiff cyclist to collide heavily with the passenger side of the vehicle.

Unfortunately, the Plaintiff’s head collided with the vehicle. The Plaintiff sustained significant spinal injuries and was rendered a quadriplegic.

Relevantly, the Plaintiff’s bicycle was fitted with a 500W capacity electric motor.

Although damages were agreed between the parties at $12 million, liability could not be agreed and the matter proceeded to trial.

The Defendants alleged that the Plaintiff cyclist was contributory negligent (that is, that they cyclist’s negligence contributed to the harm he suffered.) The alleged grounds of the Plaintiff’s contributory negligence were as follows:-

- Operating a registrable but unregistered bicycle powered by a 500W motor on the path;

- Travelling at an excessive speed;

- Failing to keep a proper lookout;

- Failing to have a horn installed on the bicycle; and

- Failing to deviate from the path rather than continue along the path across the driveway.

The Plaintiff was found contributory negligent in the order of 25% on the basis that he failed to keep a proper lookout. The other grounds were not made out.

Interestingly, the issue of the electric motor that was fixed to the bicycle was examined in some detail.

Unbeknownst to the Plaintiff, the law in the ACT required that the capacity of the electric motor not exceed 200W. The Plaintiff cyclist argued that there was no causal link between the increased capacity of his motor (500W) and the damage suffered by him. In the circumstances, he contended that there were insufficient grounds for a finding of contributory negligence on that basis.

Expert evidence was adduced at the trial showing that the bicycle’s maximum speed with the motor was no greater than 24km/hr, and that the Plaintiff cyclist had been travelling at a speed of between 15 and 20km/hr at the time of the accident. This speed was said to be similar to the speed adopted by other users of the particular bicycle path.

The Court ultimately accepted that the legality of the motor was not relevant, finding no causal link between the increased capacity and the damage suffered by the Plaintiff cyclist.

By Emily Billiau and Gemma Sweeney

R v Osborne [2014] QCA 291

Dangerous driving causing death and grievous bodily harm

In R v Osborne the Court considered the culpability of a truck driver who struck and killed one cyclist and caused serious injuries amounting to grievous bodily harm to two other cyclists.

The 65 year old truck driver had no previous convictions and only a minor traffic history. The truck driver was driving with a wide load across a bridge whereupon the cyclists were travelling in a single file. There was traffic coming from the other direction also.

It was the evidence of the truck driver at the trial of the matter that although he thought it was going to be a “tight squeeze,” he “believed there was enough room to get through.” Unfortunately, there was not. The truck struck and killed one cyclist, seriously injured two others, and caused lesser injuries to a fourth cyclist.

The driver of the truck pleaded guilty to dangerous operation of a vehicle causing death and grievous bodily harm. He was sentenced by the Court to three and a half years imprisonment, suspended after 14 months for an operational period of four years. He was also disqualified by the Court from holding or obtaining a driver’s licence for five years.

In sentencing, the Judge was of the view that the driver’s conduct constituted “a very serious error of judgement,” beyond merely “momentary inattention.”

On appeal however, the Court made the point that descriptions such as “momentary inattention: are not the critical issue. The issue for consideration rather was the level of seriousness of the actual driving. The Court also went on to reduce the sentence to three-and-a-half years imprisonment, suspended after only 9 months.

By Emily Billiau | Principal

IF YOU HAVE MORE QUESTIONS, GIVE US A CALL.

Most queries can be answered easily in under 15 minutes.

IF NOW IS NOT A GOOD TIME TO CALL...

Give us your contact details and we can ring you back to answer your questions. It's free.

Simmons v Rockdale City Council (2013) 65 MVR 141

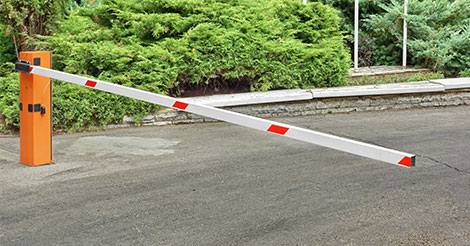

A Popular Cycling Route and the Boom Gate

The Plaintiff was a competitive cyclist who was out on an early morning training ride. The Plaintiff’s ride took him along Riverside Drive in front of the St George Sailing Club (the Club), where he collided with a closed boom gate and sustained serious injuries. The boom gate had been installed by the Council after issues with ‘hooning’ had arisen in the carpark at night.

The Council had entered into an informal agreement with the Club, allowing them to open and close the gate ‘at their discretion.

The Council’s case was that the collision had occurred as a result of the Plaintiff’s own negligence. The Council pleaded that:

- It was an obvious risk of engaging a dangerous recreational activity (cycling); and

- That the Plaintiff had failed to keep a proper lookout; and

- That the Plaintiff was riding in a direction opposite to marked traffic flow; and

- That the Plaintiff failed to ride at an appropriate speed; and

- That the Plaintiff ignored ‘no exit’ signs

Evidence lead at the trial of the matter demonstrated that the Council was aware of two earlier incidents occurring when the boom gate had been left closed early in the morning and cyclists had subsequently collided with it. There was also evidence that Riverside Drive had, for many years, served as an extension of a popular cycling route and cyclists would frequently ride through the point where the boom gate was erected.

The Plaintiff was ultimately successful in his claim, although a finding on contributory negligence was made by the Court. The Court found that the Plaintiff cyclist contributed to his injuries Judgement was entered in favour of the Plaintiff in the order of $928,000.00 (after a 20% reduction for contributory negligence) on the basis that the council owed a duty of care to regular users of the Riverside Drive, such as cyclists, and should have taken reasonable steps to ensure that the boom gate did not become a hazard. They failed to take appropriate action by not having a system in place to ensure that the gate would be opened by a specific time each day, did not make the boom gate readily visible and provided no safe alternative access to the street.

By Emily Billiau and Gemma Sweeney